Investment Risk Is Not What You Think It Is

Investing and risk are so closely aligned that they may as well be synonyms. Most people, however, significantly misunderstand the risks involved in investing.

When risk is used in regards to investing, it’s normally referring to the volatility of the stock market. This idea is reinforced by the way the media reports on financial news. “The Dow is UP! The Dow is DOWN!” It’s enough to make some investors as skittish as my neighbor’s little yappy lapdog during a thunderstorm.

In school, my investment professors reinforced this idea of volatility as risk using the measurement standard deviation. This measures volatility of an investment – how far the change in value varies from its average change – but is almost universally referred to as “risk.” When I began working with real investors, however, my view of this changed. I no longer believe volatility is inherently risky.

Warren Buffett argued this in his 2014 annual shareholder letter. Referencing the idea that a well-diversified but volatile stock portfolio may actually be less risky than traditionally “safer” investments, he stated:

That lesson has not customarily been taught in business schools, where volatility is almost universally used as a proxy for risk. Though this pedagogic assumption makes for easy teaching, it is dead wrong: Volatility is far from synonymous with risk. Popular formulas that equate the two terms lead students, investors and CEOs astray.

A Pesky Neighbor

Imagine for a moment that every day when you get home from work your neighbor comes to your fence, leans over, and says, “You know, bud, today I’d pay you this much if you sold your house to me.” And he names his price. The next day he does the same. And the next. Every day he comes over and tells you how much he’d pay you if you sold your house to him right away. Some days his price is up; some days his price is down. Who knows how he picks his price.

Other than getting on your nerves, this kind of feedback would have an effect on your thinking over time. If he ran over to you one day with his hair on fire telling you that he’d only give you a fraction of what he would’ve paid the day before, you might freak out some too. If he greedily came over and announced he’d pay you 30% more than he thought your house was worth the day before, you might get greedy and take the offer.

This is what the stock market does. Every day it reports to you on the real “value” of your investment. Many days it’s the same as the day before. Some days have dramatic swings. But just like your house, the volatility only matters if it’s time to sell.

Volatility does become a risk if it’s time to sell some of your investments. For example, some homeowners found themselves in trouble because a job transfer or other life event forced them to sell their house in the housing market crash of 2008. The same thing happened to many investors who retired in 2008 and needed to liquidate stocks to replace their paychecks.

Reducing the Risk

But there are ways to mitigate this type of risk. For example, let’s say instead of your personal home, the house your neighbor is offering to buy daily is a rental property. It would operate more like a business, with a stream of income from renters, expenses like taxes and repairs, and profit left over. This example would be much more like stock investing anyway, because investing in stock is ultimately owning businesses.

In this rental property example, there would have been many ways to mitigate the volatility risk of a 2008 housing downturn. The first thing that you could do would be to ignore the neighbor. If the house was purchased as a rental and was providing the desired stream of income, why would his opinion matter today anyway? The second way you could have alleviated the risks would have been to build up cash reserves. Having cash on hand would have made sure you could have paid for any major repairs or weathered a period in between renters. If you had enough cash on hand, you might have even contemplated buying another property at this time because they were effectively on sale!

The reason you can ignore your neighbor is that the underlying nature of your rental property business has not changed. You’re still collecting rent and know that short-term value of your property is much less important that what it will be worth in the long term. Investing, like business, takes this long term perspective as well.

The long term view

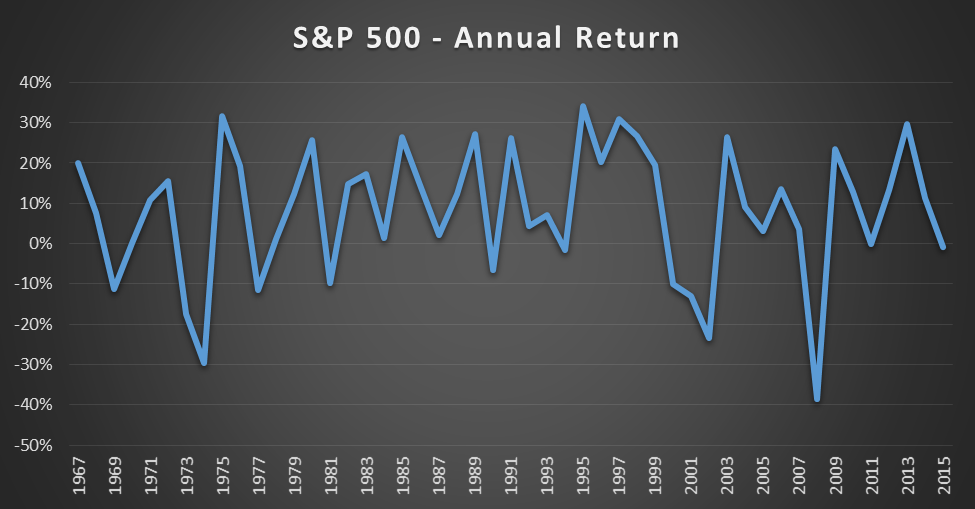

Let me demonstrate with another example. The chart below is a visualization of the last 50 years’ worth of annual returns of the S&P 500 index, a popular proxy for the U.S. stock market.

Annual return of S&P 500 from 1966-2015. Source: Yahoo Finance:

The chart above highlights the volatility of the market. Notice how up and down it is. This is what I believe most people hear when the TV tells them the daily market movements. It feels like there’s no pattern at all. This craziness, when internalized, is what causes the skittishness and nervousness.

It would be easy to misread the data in this chart and assume that after 50 years of gains and losses, you’re right back where you started. This is grossly misleading. The actual average return for that period is 7.78%. If you had invested $1,000 in December of 1965 and held it until December of 2015, your investment would have been worth over $22,000 (a cumulative return of 2,100%).

Just like our imaginary rental property, this investment would have also been kicking out income in the form of dividends. The dividends over that time period would have equaled over $7,300 (seven times the original investment). And, finally, if you had re-invested those dividends back into the S&P 500 over that time period instead of spending them, your initial investment of $1,000 would have grown to over $95,000.

Real Risks to Guard Against

That’s not to say there aren’t real risks involved with investing. Just like our home ownership example, there are real dangers that can throw your investment plans awry. Careful planning can mitigate most of these risks however. Most investment risks can be included in these categories:

- Market risk: This is the risk that the entire market could experience a downturn, causing systematic price decreases. It causes price changes that aren’t unique to the particular investments you own but affect everything in the economy. In our housing example, the 2008 housing crisis is a case in point. In general, housing prices across the entire US went down, but if your house decreased in value, it wasn’t because the house itself had issues. Some neighborhoods were hit harder, but some barely noticed a difference at all. How to protect yourself: As referenced above, the best way to protect yourself is to avoid putting yourself in a position where you need to sell at an importune time. This means not holding short-term dollars in a long-term investment. Reducing this type of risk is what this entire post is about.

- Business risk: This is the risk that specific businesses or industries get into financial trouble. Shareholders of Eastman Kodak succumbed to this risk in the late 1990s when Kodak failed to adapt to a digital marketplace. In our rental property business example, the similar risk would have come from potential issues in the home we purchased, like major repair problems or changing demographics of our neighborhood making that area undesirable for renters. How to protect yourself: Just like our little rental property business, the best way to mitigate this risk is by diversifying. For example, if an investor owned an index fund of the entire stock market during the late 90s, that investor would have profited from the hundreds of companies that profited from the shift to digital photography.

- Liquidity risk: This is the risk that you cannot sell your investment when needed. This is common with non-traded investments like REITs and Limited Partnerships. It’s as if the annoying neighbor stopped coming to your house just when you wanted to off-load it. Many desperate homeowners in the housing crash had to slash their asking price even below the regular market dip, just to off-load their property in a slow environment. How to protect yourself: Avoiding highly illiquid assets like non-traded investments and businesses. Investment tools like Exchange Traded Funds now allow investors to get into almost any type of investment without going through extreme illiquidity. Leaving a long runway before you need cash back – not letting yourself get painted into a financial corner – may lessen the risk when non-traded opportunities are a must-have.

- Longevity risk: Investing is long-term in nature, but this is the risk that the buying power of your money diminishes over time due to inflation. For example, if an investment gains 2% annually, but the cost of everything else goes up annually 3% over that same time period, the investment has actually lost money. It might look positive on paper, but the real value of your money has actually gone backwards. This inflation risk is especially dangerous over longer periods, when inflation is given time to do its work. For instance, our $1,000 invested in 1965? It would have taken almost $7,600 in 2015 to buy the same amount of stuff that you could’ve in the 60s. How to protect yourself: By investing in appreciating assets, like businesses, you can take advantage of the cost of goods going up. Since businesses hold assets of real, tangible value (their products, office buildings, contracts with buyers, etc), their total value (share price) tends to get a boost from inflation rather than be eroded.

Your Own Planning

You can plan ahead to reduce the chance that volatility will become a risk for you. Through careful planning, building cash reserves, and staying properly diversified, you may be able to turn the volatility of the markets into an advantage for yourself. The key is making sure your investments align appropriately to your own, specific long-term financial plan. So tune out your nosy neighbor, whether he comes to you in the form of CNBC, Fox Business, or Bloomberg. Instead, make sure you build your plan and stick to it.

“There are two main dangers in life: risking too much and risking too little.” – Jimmy Chin

< Back to Insights