Can investing save the world? A case for impact investments

It seems that everyone likes to hate on business lately. Politicians rail against corporate interests and Wall Street greed. In pop culture, the bad guys are almost always in suits and ties. One recent TV show pitted its hero against a conglomerate simply called “Evil Corp.”

Yet there is a growing movement to redeem business and reframe its powers for good. These people believe that business is a powerful engine for change, and that it is uniquely positioned to address some of the world’s most intractable problems.

You might ask, “Isn’t that what charities are for?” Yes, charitable efforts seek to address societal problems and serve those around us who need the most help. But nonprofits have their limitations, too. Most charities rely on a (hopefully) never-ending stream of good will. Donations must be solicited and sent in year-over-year, and often from the same donors. These nonprofits are doing a lot of good in the world, but the donations-only model can cause problems for both the charities and the donors.

I spoke with a major philanthropist once who realized that his giving had grown to the point that a number of charities’ budgets depended on him. If his personal ability or desire to give changed, the work of those charities would slow down. They would have to reduce their services, limit their work and even lay people off.

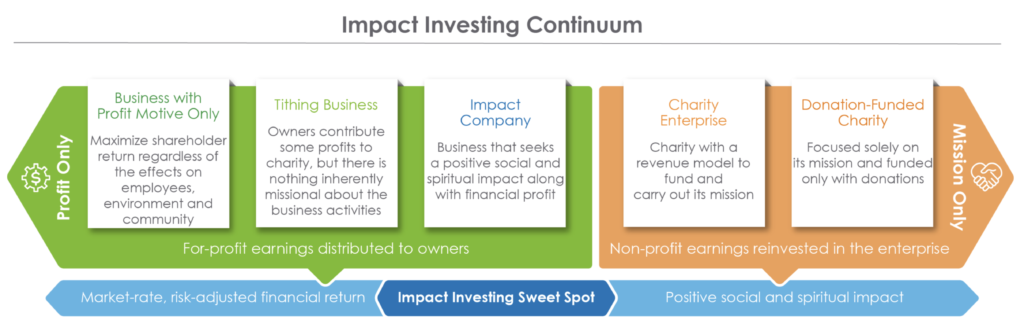

Rather than energizing him, his charitable work began to discourage him because he believed his current giving level was unsustainable. He was worried about what would happen to the charities when he was no longer able to keep them going. Some charities are tackling their dependence on donors by creating revenue-generating enterprises within their organizations. And reaching across the business/charity divide from the other direction are what some call “impact companies,” or for-profit businesses that also pursue social and spiritual good.

Why combine business with doing good? In the book Social Impact Investing: New Agenda In Fighting Poverty, Kim Tan and Brian Griffiths argue that economic growth—not foreign aid or charitable giving— spurred China’s rise out of extreme poverty. (In 1990, 61 percent of China’s population lived on less than $2 per day; today, only 4 percent do.) Tan and Griffiths say that business can make really big changes happen. The authors encourage investors to put that economic engine to work by supporting “for-profit business with measurable social outcomes that intentionally and primarily addresses the social needs of the poor and marginalised.”

What does that actually look like? One example is the Sunshine Nut Co., which runs on a “quadruple bottom line business model” to achieve financial, environmental, social and transformational results in Mozambique. The company pays fair wages to growers and factory workers and produces in an environmentally responsible way. It gives 30 percent of its profits to regional agricultural development, 30 percent to local orphan care and 30 percent to helping start similarly impactful new food companies in the area.

Impact companies like the Sunshine Nut Co. have sustainable business models that aren’t reliant on charitable gifts. They make money and intentional social change. That’s why they are attractive to investors who want to both steward their resources wisely and do good in the world. That’s a really different way of evaluating a potential investment’s return. And a really different way of supporting social change:

- Impact investing provides for solutions that are deeper and wider than charity alone.

- Impact investing is more sustainable in addressing (some) problems than donation-funded solutions.

- Impact investing releases different pockets of money than either philanthropy or traditional investing alone accesses.

Impact investing is not for everyone. Coupling social initiatives with investing has the potential to increase risk of failure or decrease returns available to investors. At the moment, these types of investments are largely private (there are not many “funds”), so they tend to require larger amounts of money to get started. But if you’re intrigued, here are a few ways I’ve seen people get started:

- Start small. Impact investing is not an all-or-nothing thing. Some have started by dedicating 10 percent of their portfolio or net worth to impact companies.

- Put DAF dollars to work. Donor Advised Fund and private foundation dollars are usually invested in traditional models until they’re ready to be sent out for good. Using these funds for impact investing is a way to do both at once.

- Find what works for you. There are many types of investments in this space, from loans to a charity starting a business, to private equity stakes in for-profit companies. There are even CD style savings accounts which provide capital to expanding churches. Take your time to find the mechanism that fits your investing style and passion for change.

Jonathan serves on the board of Impact Foundation, a nonprofit that helps bring together the best of business and the best of charity to accomplish a meaningful mission. Reach out to him to start the conversation and learn more about impact investing.

< Back to Updates